|

The Lakeview Gusher (click here to view the Lakeview photo gallery)

Julius Fried, a grocer by trade, picked the site for the Lakeview well because he thought a clump of red grass indicated good oil land. When Fried and his partners naively spudded their well in the axis of a syncline on New Years day in 1909, hopes ran high. Yet drilling progressed slowly, and their company went broke when the well reached only 1,655 feet. Neighboring Union Oil offered to help by taking over the drilling operations, but only in their spare time when crews were available.

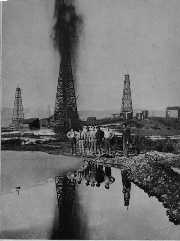

A roaring column of sand and oil twenty feet in diameter and two-hundred feet high gushed into the air, and issued a stream of oil at its base, dubbed the "Trout Stream" which flowed down every adjacent ditch and gully. Rather than diminishing in force, the gusher grew stronger each day and eventually buried the engine house in a mountain of sand. Although the wooden derrick remained standing a few weeks longer, eventually it too, and all the drilling equipment as well, were completely swallowed up by a huge crater that formed around the drill well. Torrents of oil poured from the wild well, and hundreds of men worked round the clock building sandbag dams to contain the crude in twenty large, open-air sumps. The flow continued unabated, and thirty days after the well first blew in the flow was estimated at 90,000 barrels a day. The Lakeview No. 1 quickly became America's most famous gusher. A four-inch pipeline leading to eight 55,000 barrel tanks, about 2-1/2 miles away, was installed in the amazingly short time of four hours. From the tanks, an eight-inch line carried the oil to Port Avila on the California coast.

Despite precautions, a nearby well known as "Tightwad Hill", blew out and caught fire midway through the life of the Lakeview gusher. Apparently, light from the fire of the Tightwad was so bright that tourists were able to view the distant Lakeview gusher even at night. In desperation, a wooden box of massive timbers was pulled over the gusher with heavy cables, but oil still spurted out at 48,000 barrels a day. Eventually, this box too was destroyed by a huge crater that formed with a central cone of sand thirty feet high. The gusher was finally brought under control on October, 1910 by building an embankment of sandbags, a hundred-feet in diameter, around the well and its crater. When this embankment reached a height of twenty feet, it created an oil pool over the crater that was deep enough to reduce the oil flow from an uprushing column to a gurgling spout. When the bottom of the hole caved in on September 10, 1911, the well died. Although Lakeview No. 1 produced 9.4 million barrels during the 544 days it flowed, less than half of this oil was saved-the rest evaporating off or seeping into the ground.

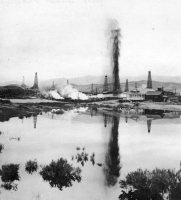

Of the offset wells drilled, only Lakeview No. 2 in May, 1914 found oil, but it was from a different sand at a depth of 2,622 feet. Lakeview No. 2 did come in a gusher, but it was not anywhere near as big as Lakeview No. 1. Nonetheless, it did flow 1700 barrels a day, and it produced 38,376 barrels of oil and 15,000 barrels of emulsion before the 4-1/2 inch casing collapsed just above the oil sand. The picture here shows Lakerview No. 2 on May 20, 1914. Easily missed, the Lakeview reservoir was described as a "narrow, oil-filled channel of sandstone, a few feet wide by a mile long". One interpretation is that the sand is a linear channel that is surrounded by shale and cuts down into into an underlying unconformity near where the tip of Calitroleum sand laps out onto the unconformity. Another possibility is that the reservoir is a vertical sandstone dike that connects to the underlying Lakeview sand, but not into other sandstones. Irrespective of the nature of the sand, the Lakeview No. 1 nust have missed it by several feet, as the well drilled nothing but shale. Nonetheless, fluid pressures in the nearby sand were so great that oil was able to force its way out through the enclosing shale and into the well bore to create the greatest gusher California has ever known. One question that is always asked is which gusher was the biggest - Lakeview No. 1, Spindletop, or the 2010 Gulf oil spill. Here are the facts. The Lakeview Gusher spilled 9.4 million barrels (395 million gallons) for 18 months with a peak rate of 125,000 barrels/day. Spindletop spilled 900,000 barrels for 9 days at an average rate of 100,000 barrels/day, afterwhich the well was capped to become a producer, and the Gulf gusher leaked 4.9 million barrels (185 million gallons) for 65 days at a peak rate of 62,000 barrels/day. Of course, the Lakeview was but one of many spectacular gushers that blew out in the San Joaquin Valley in the early years of the oil industry.

Picture Gallery of the Lakeview Gusher

|

|