|

|

The History of the Oil Industry

(with an emphasis on California and the San Joaquin Valley)

click any of the pictures below for a better view

Oil Through the Ages

|

| 347 A.D. |

Oil wells are drilled in China up to 800 feet deep using bits attached to bamboo poles. |

| 1264 |

Mining of seep oil in medieval Persia witnessed by Marco Polo on his travels through Baku. |

| 1500s |

Seep oil collected in the Carpathian Mountains of Poland is used to light street lamps. |

| 1594 |

Oil wells are hand dug at Baku, Persia up to 35 meters (115 feet) deep. |

| 1735 |

Oil sands are mined and the oil extracted at Pechelbronn field in Alsace, France. |

| 1802 |

A 58-ft well is drilled using a spring pole in the Kanawha Valley of West Virginia by the brothers David and Joseph Ruffner to produce brine. The well takes 18 months to drill. |

| 1815 |

Oil is produced in United States as an undesirable by-product from brine wells in Pennsylvania. |

| 1848 |

First modern oil well is drilled in Asia, on the Aspheron Peninsula north-east of Baku, by Russian engineer F.N. Semyenov. |

| 1849 |

Distillation of kerosene from oil by Canadian geologist Dr. Abraham Gesner. Kerosene eventually replaces whale oil as the illuminant of choice and creates a new market for crude oil. |

| 1850 |

Oil from hand-dug pits in California at Los Angeles is distilled to produce lamp oil by General Andreas Pico. |

| 1854 |

First oil wells in Europe are drilled 30- to 50-meters deep at Bóbrka, Poland by Ignacy Lukasiewicz. |

| 1854 |

Natural Gas from a water well in Stockton, California is used to light the Stockton courthouse. |

| 1857 |

Michael Dietz invents a kerosene lamp that forces whale oil lamps off the market. |

| 1858 |

First oil well in North America is drilled in Ontario, Canada. |

| 1859 |

First oil well in United States is drilled 69 feet deep at Titusville, Pennsylvania by Colonel Edwin Drake. |

|

California Comes of Age

|

| 1861 |

First oil well in California is drilled manually in Humboldt County. |

| 1866 |

Oil is collected from tunnels dug at Sulphur Mountain in Ventura County by the brothers of railroad baron Leland Stanford, the same year that these techniques are applied to the Pechelbronn oil mine in France. |

| 1866 |

First steam-powered rig in California drills an oil well at Ojai, not far from the Sulphur Mountain seeps. |

| 1875 |

First commercial oil field in California is discovered at Pico Canyon in Los Angeles County. |

| 1878 |

Electric light bulb invented by Thomas Edison eliminates demand for kerosene, and the oil industry enters a recession. |

| 1885 |

Gas wells are drilled in Stockton, California for fuel and lighting. |

| 1885 |

Oil burners on steam engines in the California oil fields, and later on steam locomotives, create new crude oil markets. |

| 1886 |

Gasoline-powered automobiles introduced in Europe by Karl Benz and Wilhelm Daimler create additional markets for California oil. Prior to the automobile, gasoline was a cheap solvent produced as a byproduct of kerosene distillation. |

| 1888 |

A steel-hulled tanker sails from Ventura to San Francisco, eleven years after the 1877 sailing of a Russian tanker across the Caspian sea at Baku. |

| 1899 |

Discovery of Kern River oil field propels Kern County to top oil-producing region in state. |

Bakersfield, 1933

The San Joaquin Valley Oil Industry

- 1860s to 1890s - Tar Pits and Tunnels

- 1864 - Tar mined from open pits at Asphalto (McKittrick) on west side of San Joaquin Valley.

- 1866 - First refinery in Kern County built near McKittrick tar pits to process kerosene and asphalt.

- 1878 - First wooden derrick in Kern County constructed at Reward to drill for flux oil to mix with asphalt.

- 1887 - "Wild Goose" well at Oil City, Coalinga comes in at 10 bbls/day, demonstrating potential of north part of basin.

- 1889 - Oil wells drilled at Old Sunset (Maricopa) with a steam-powered rig mark discovery of Midway-Sunset field.

- 1893 - Railroad reaches McKittrick, where tunnels and shafts are dug to mine asphalt.

- 1894 - Old Sunset (Maricopa) part of Midway-Sunset has 16 wells producing 30 barrels of oil per day.

- 1890s to 1920s - Gushers and Cable Tools

- 1896 - Shamrock Gusher blows in at McKittrick and hastens end of tar mining operations.

- 1899 - Hand-dug oil well discovers Kern River field and starts an oil boom in Kern County.

- 1902 - Arrival of railroad makes development of Midway-Sunset field economically feasible.

- 1902 - First rotary rig in Califonia reportedly drills a well at Coalinga field, but the hole is so crooked that a cable tool is used to redrill the well.

- 1903 - Kern River and Midway-Sunset production makes California the top oil producing state.

- 1904 - 17.2 million bbls of oil produced at Kern River exceeds annual production from Texas.

- 1908 - Rotary drilling rigs and crews arrive in California from Louisiana and successfully drill wells at Midway-Sunset field and erase the embaressment of the Coalinga experiment six years earlier.

- 1909 - Midway Gusher blows out near Fellows and focuses attention on Midway-Sunset field.

- 1910 - Lakeview Gusher blows in near Taft and becomes America's greatest oil gusher.

- 1919 - Hay No. 7 catches fire at Elk Hills and becomes America's greatest gas gusher.

- 1929 - Blowout prevention equipment becomes mandatory on oil and gas wells drilled in California.

- 1930s to 1950s - Well Logs, Seismic, and Rotary Drilling

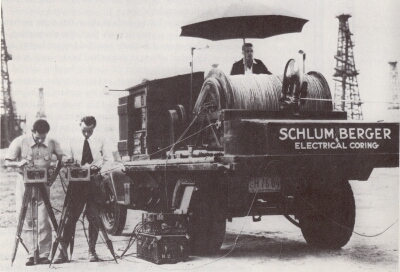

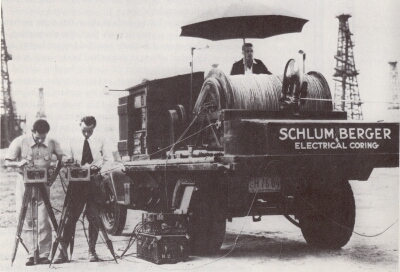

- 1929 - First well logs in California run by Shell in a well near Bakersfield (Kern County).

- 1930 - Deepest well in the world is Standard Mascot #1, rotary drilled to 9,629 feet at Midway-Sunset.

- 1936 - First seismic exploration in California discovers Ten Section field near Bakersfield. Seismic discovery of the productive Paloma and Coles Levee anticlines soon follows

- 1943 - Deepest well in the world is Standard 20-13, drilled to 16,246 feet at South Coles Levee.

- 1953 - Deepest well in the world is Richfield 67-29 drilled to 17,895 feet at North Coles Levee.

- 1960s to Today - Steam, Horizontal Wells, and Computers

- 1961 - First steam recovery projects in Kern County start up at Kern River and Coalinga fields after a successful pilot by Shell at Yorba Linda field in Los Angeles.

- 1973 - Tule Elk and Yowlumne fields become the last 100-million barrel fields discovered in Kern County.

- 1980 - First horizontal well in Kern County is Texaco Gerard #6 in fractured schist at Edison field.

- 1980s - Cogeneration hastens the spread of steam recovery projects, which dramatically ramp up oil production.

- 1985 - Kern County reaches an all-time production high of 256 million barrels of oil/year. At the same time, California reaches an all-time production high of 424 million barrels of oil/year.

- 1990s - 3D-seismic data and 3D-computer modeling of reservoirs bring new life to old fields.

- 1997 - Deepest horizontal well in Kern County is Yolwumne 91X-3 with measured depth of 14,300 feet. However, the well is surpassed only two years later by the relief well for the Bellevue blowout.

- 1998 - A blowout and oil well fire at the Bellevue #1 wildcat in the East Lost Hills subthrust fuels hopes for the first major Kern County discovery in over a decade. However, subsequent drilling proves to be a disappointment.

And throughout much of this San Joaquin Valley oil history, members of the

San Joaquin Geological Society were holding monthly dinner meetings and sharing a beer with the likes of Senteur de Boue. Click here to learn more about the history of this esteemed organization.

|

The Oil Industry of Medieval Persia (Azerbaijan and Baku)

When Marco Polo in 1264 visited the Persian city of Baku, on the shores of the Caspian Sea in modern Azerbaijan, he saw oil being collected from seeps. He wrote that "on the confines toward Geirgine there is a fountain from which oil springs in great abundance, inasmuch as a hundred shiploads might be taken from it at one time." In addition to oil seeps, Marco Polo also saw spectacular mud volcanos, sourced by natural gas seeping through ponds, and a flaming hillside, the "Eternal Fires of the Apsheron Peninsula", a spit of land that juts eastward from Azerbaijan into the Caspian Sea and where condensate and natural gas seeping through fractured shales has burned, and been worshipped, for centuries. The thumbnail on the right shows the Temple of the Fire Worshipers at Ateshkah where a gas seep has burned since ancient times. When Marco Polo in 1264 visited the Persian city of Baku, on the shores of the Caspian Sea in modern Azerbaijan, he saw oil being collected from seeps. He wrote that "on the confines toward Geirgine there is a fountain from which oil springs in great abundance, inasmuch as a hundred shiploads might be taken from it at one time." In addition to oil seeps, Marco Polo also saw spectacular mud volcanos, sourced by natural gas seeping through ponds, and a flaming hillside, the "Eternal Fires of the Apsheron Peninsula", a spit of land that juts eastward from Azerbaijan into the Caspian Sea and where condensate and natural gas seeping through fractured shales has burned, and been worshipped, for centuries. The thumbnail on the right shows the Temple of the Fire Worshipers at Ateshkah where a gas seep has burned since ancient times.

Shallow pits were dug at the Baku seeps in ancient times to facilitate collecting oil, and hand-dug holes up to 35 meters (115 feet) deep were in use by 1594. These holes were essentially oil wells, which makes Baku the first true field. Apparently 116 of these wells in 1830 produced 3,840 metric tons (about 710 to 720 barrels) of oil. Later, Russian engineer F.N. Semyenov used a cable tool in 1844 to drill an oil well near the Bibi-Eibat (Bibi-Heybat) embayment on the Apsheron Peninsula, ten years before Colonel Drake's famous well in Pennsylvania. Also, offshore drilling started up at Baku at Bibi-Eibat near the end of the 19th century, about the same time that the "first" offshore oil well was drilled in 1896 at Summerland field on the California Coast. The thumbnail on the left shows workers digging an oil well by hand at Bibi-Eibat. Shallow pits were dug at the Baku seeps in ancient times to facilitate collecting oil, and hand-dug holes up to 35 meters (115 feet) deep were in use by 1594. These holes were essentially oil wells, which makes Baku the first true field. Apparently 116 of these wells in 1830 produced 3,840 metric tons (about 710 to 720 barrels) of oil. Later, Russian engineer F.N. Semyenov used a cable tool in 1844 to drill an oil well near the Bibi-Eibat (Bibi-Heybat) embayment on the Apsheron Peninsula, ten years before Colonel Drake's famous well in Pennsylvania. Also, offshore drilling started up at Baku at Bibi-Eibat near the end of the 19th century, about the same time that the "first" offshore oil well was drilled in 1896 at Summerland field on the California Coast. The thumbnail on the left shows workers digging an oil well by hand at Bibi-Eibat.

Baku was known for spectacular gushers, and spectacular well fires as well - an example of which is shown in the still on the right from a short film by the Lumière Brothers in 1896. The first of the big spouters blew out in 1873 on the Balakhani Plateau, which was the high ground of the Apsheron Peninisula, beneath which lies a giant anticline that is responsible for the prolific oil production. The Balakhani field during the 1870s was the largest oil field in the world. Another giant anticline at the Bibi-Eibat embayment, on the south side of the peninsula, extends from the land out to beneath the waters of the bay. A string of huge onshore producers, beginning with the Tagiev spouter in the mid-1880s, elevated Bibi-Eibat to the largest field. Russian engineers, realizing that production extended offshore, began filling and draining the bay in 1909 to allow continued drilling. Over 300 hectares (741 acres) had been reclaimed by 1927, a project said to be second in magnitude only to construction of the Panama Canal. Baku was known for spectacular gushers, and spectacular well fires as well - an example of which is shown in the still on the right from a short film by the Lumière Brothers in 1896. The first of the big spouters blew out in 1873 on the Balakhani Plateau, which was the high ground of the Apsheron Peninisula, beneath which lies a giant anticline that is responsible for the prolific oil production. The Balakhani field during the 1870s was the largest oil field in the world. Another giant anticline at the Bibi-Eibat embayment, on the south side of the peninsula, extends from the land out to beneath the waters of the bay. A string of huge onshore producers, beginning with the Tagiev spouter in the mid-1880s, elevated Bibi-Eibat to the largest field. Russian engineers, realizing that production extended offshore, began filling and draining the bay in 1909 to allow continued drilling. Over 300 hectares (741 acres) had been reclaimed by 1927, a project said to be second in magnitude only to construction of the Panama Canal.

check out the links below

to learn more about the oil history of Azerbaijan

www.azer.com

Historic Photos of the Baku Oil Industry

Spouters and Fountains of Baku

|

Modern offshore wells on the Aspheron Peninsula

are shown on the left.

You can see more Baku oil pictures

by clicking here |

The Early Oil Industry of Poland and Romania

The Carpathian Mountains in Poland abound in oil seeps, and Carpathian oil, hand dipped from pits dug in front of the seeps, was burned in street lamps, as early as the 1500s, to provide light in the Polish town of Krosno. Unfortunately, the seep oil was a dark, viscous liquid that stuck to everything. It also burned with a foul smell and gave off more smoke and soot than other lamp oils, most of which were rendered from animal fat.

Ignacy Lukasiewicz, a Polish druggist in the modern Ukranian town of Lvov, saw the potential of using seep oil in lamps as a cheap alternative to expensive whale oil. To make a clean-burning fuel, he began experimenting with distillation techniques, perfected earlier by Dr. Abraham Gesner in Canada, to produce clear kerosene from smelly seep oil. His experiments gained notoriety, and the European oil industry was born on a dark night on July 31, 1853 when Lukasiewicz was called to a local hospital to provide light from one of his lamps for an emergency surgery. Impressed with his invention, the hospital ordered several lamps and 500 kg of kerosene. Lukasiewicz enlisted the aid of a business partner and traveled to the Vienna, capitol city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to register his distillation process with the government on December 31, 1853.

Ignacy Lukasiewicz, a Polish druggist in the modern Ukranian town of Lvov, saw the potential of using seep oil in lamps as a cheap alternative to expensive whale oil. To make a clean-burning fuel, he began experimenting with distillation techniques, perfected earlier by Dr. Abraham Gesner in Canada, to produce clear kerosene from smelly seep oil. His experiments gained notoriety, and the European oil industry was born on a dark night on July 31, 1853 when Lukasiewicz was called to a local hospital to provide light from one of his lamps for an emergency surgery. Impressed with his invention, the hospital ordered several lamps and 500 kg of kerosene. Lukasiewicz enlisted the aid of a business partner and traveled to the Vienna, capitol city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to register his distillation process with the government on December 31, 1853.

To provide oil for his kerosene business, Lukasiewicz initially collected a thick, sticky crude from shallow, hand-dug wells in the Gorlice region, an area in the Carpathians about 50 miles west of the Polish town of Bóbrka. The following year, he teamed up with Titus Trzecieski and Mikolaj Klobassa to establish an "oil mine" in Bóbrka which pumped crude oil from hand-drilled, 30- to 50-meter deep wells. Later, wells as deep as 150 meters were drilled that produced a lighter, better-quality crude from which to distill kerosene. Other entrepreneurs dug their own wells,and a thriving Polish oil industry developed, which was followed in 1857 by the drilling of wells at Bend, northeast of Bucharest, on the Romanian side of the Carpathians. Two years later, Colonel Edwin Drake, who perhaps had knowledge of the Polish developments, drilled his famous well in Pennsylvania, an event wrongly labeled by many in the industry as the drilling of the "first oil well".

To provide oil for his kerosene business, Lukasiewicz initially collected a thick, sticky crude from shallow, hand-dug wells in the Gorlice region, an area in the Carpathians about 50 miles west of the Polish town of Bóbrka. The following year, he teamed up with Titus Trzecieski and Mikolaj Klobassa to establish an "oil mine" in Bóbrka which pumped crude oil from hand-drilled, 30- to 50-meter deep wells. Later, wells as deep as 150 meters were drilled that produced a lighter, better-quality crude from which to distill kerosene. Other entrepreneurs dug their own wells,and a thriving Polish oil industry developed, which was followed in 1857 by the drilling of wells at Bend, northeast of Bucharest, on the Romanian side of the Carpathians. Two years later, Colonel Edwin Drake, who perhaps had knowledge of the Polish developments, drilled his famous well in Pennsylvania, an event wrongly labeled by many in the industry as the drilling of the "first oil well".

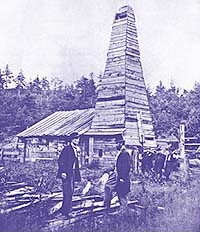

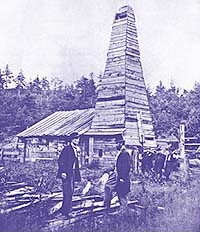

Bobrka oil field, Poland in 1872

Many of these early wells were laboriously dug by hand. Others were drilled with spring poles, in which a springy wooden pole was stuck in the ground at an angle and a heavy metal drill bit attached by a cable to the head of the pole. Operators would bounce up and down on stirrups attached to the pole, causing the bit to literally chop a hole into the hard ground. The hole was cleaned by lowering into the hole a specially designed bucket, called a bailer, which was similarly bounced up and down until it filled dirt and cuttings to be hauled to the surface.

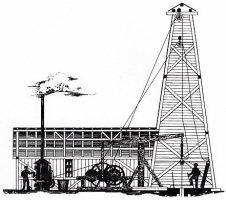

Steam engines were employed to mechanically drill wells in the Pennsylvania oil fields during the U.S. Civil War, and Thomas Bard imported a steam-powered drilling rig and crew from Pennsylvania to successfully drill a mediocre oil well in California in 1865. Steam was first used in Poland two years later in 1867 to drill a well at Kleczany, 60 kilometers west of the Bóbrka field. Steam-powered drilling made its debut at Bóbrka a few years later, sometime between 1870 and 1872, and enabled operators to drill much deeper than they had been able to previously. Within a few years virtually all oil wells, in both the United States and Europe, were being drilled mechanically.

(Excerpted from various issues of the AAPG Explorer)

Polish Oil Wells - Derricks for hand-dug wells at Bobrka field are on the left,

and the derrick for a steam-driven operation at Bitkow field is on the right.

The Early Oil Industry of Pennsylvania

Oil Creek in western Pennsylvania abounds in oil seeps that ooze thick black crude into the stream. These seeps were well known to the Seneca Indians, one of the Iroquois Nation tribes, who used the oil as a salve, mosquito repellent, purge and tonic. Many settlers also believed that these oils were medicinal, and "hawkers" sold bottles of it, as early as 1792, as a cure-all called "Seneca Oil". The nearby Allegheny and Kiskiminetas river valleys had oil also, but beneath the ground, where as early as 1815 it was contaminating several of the brine wells that supplied a booming salt industry in the Pittsburgh area. Oil Creek in western Pennsylvania abounds in oil seeps that ooze thick black crude into the stream. These seeps were well known to the Seneca Indians, one of the Iroquois Nation tribes, who used the oil as a salve, mosquito repellent, purge and tonic. Many settlers also believed that these oils were medicinal, and "hawkers" sold bottles of it, as early as 1792, as a cure-all called "Seneca Oil". The nearby Allegheny and Kiskiminetas river valleys had oil also, but beneath the ground, where as early as 1815 it was contaminating several of the brine wells that supplied a booming salt industry in the Pittsburgh area.

In the early 1850s, a Pittsburgh druggist named Samuel Kier began selling bottled oil from his father's brine wells as "Pennsylvania Rock Oil", but met with little success. One day, Colonel A. C. Ferris, a whale oil dealer, processed a small amount of Kier's "tonic" to make a lighter oil that burned well in a lamp. When Kier heard about this, he began using a one-barrel whiskey still of his own to convert his rock oil into lamp oil. After Kier upgraded his still to five-barrel capacity, Pittsburgh forced him to move his operation to a suburb out of fear of an explosion.

When George Bissell, a New York lawyer, learned of Kier's operation, he hired Benjamin Silliman Jr of Yale University, probably around 1854, to see if Seneca Oil would yield lamp oil. Silliman successfully distilled the oil into several fractions, including an illuminating oil already known as kerosene. Armed with Silliman's results, Bissell received financial backing to form the "Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company", which later became the "Seneca Oil Company".

An unemployed railroad conductor and express agent named Edwin Drake, who by chance was staying at the same hotel in New Haven, Connecticut as Bissel and his partners, was hired in 1857 to visit Titusville, a town on Oil Creek. Drake's only qualification for this assignment was a free railroad pass remaining from his previous job. Although Drake had never been in the military, when he returned to Titusville the following year to commence operations as a Seneca Oil Company agent, his employers passed him off as a colonel to give their venture an air of respectability.

Historically, oil was collected at Oil Creek by damming the creek near a seep, then skimming oil off the top of the resulting pond. Drake tried this at a seep once used by a sawmill to produce oil for lubricating the mill machinery, but even with improvements and opening up other seeps in the area, he only increased production from three or four gallons to a still non-economic six to ten gallons a day. Next workers tried digging a shaft to mine the oil, but groundwater flooded in too quickly for the workers to continue. Finally, Drake decided to drill a well and locate the source of the seep oil, using the same steam-powered equipment used to drill brine wells.

He hired a blacksmith named "Billy" Smith, who had drilled brine wells for Kier and others in the Pittsburgh area. Smith, with his son Samuel, began drilling in the summer of 1859. Although progress was slow, usually three feet a day in shale bedrock, they reached a depth of 69½ feet by August 27, just as Drake was reaching the last of his funds. When Billy and Samuel pulled their drilling tools from the well the next morning, they noticed oil rising in the hole. After installing a hand-operated lever pump borrowed from a local kitchen, the first days production was about twenty-five barrels. Production soon dropped off to a steady ten barrels or so a day, and the well is said to have continued at that rate for a year or more.

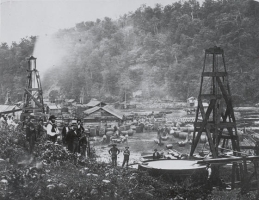

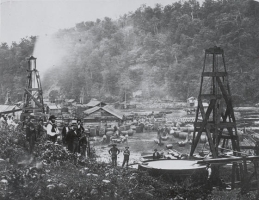

Although Drake's well was no gusher, it was the beginning of an idea. Titusville transformed almost overnight from a quiet farm town to an oil boom town of muddy roads, hastily constructed wooden derricks, and noisy steam engines. The Pennsylvania oil boom was on.

The Woodford (left) and Phillips (right) wells in the Oil Creek Valley of Pennsylvania about 1862 (Oil Creek flows just to the right of the Phillips well). The Phillips well was the most productive oil well of its time, initially at a rate of 4,000 barrels of oil per day in October, 1861. The Woodford came in at 1,500 barrels per day in July, 1862.

|

check out the links below

to learn more about the early oil history of the United States

Early Days of Oil by Paul H. Giddens, 1948, 7 p.

Index to Early Petroleum History sites

Petroleum History Institute

(formerly oilhistory.com by Samuel Pees)

Petroleum Education - History of Oil

The Early Oil Industry of Texas

click here to learn about

The Spindletop Gusher

and the Birth of the Texas Oil Industry

|

|

When Marco Polo in 1264 visited the Persian city of Baku, on the shores of the Caspian Sea in modern Azerbaijan, he saw oil being collected from seeps. He wrote that "on the confines toward Geirgine there is a fountain from which oil springs in great abundance, inasmuch as a hundred shiploads might be taken from it at one time." In addition to oil seeps, Marco Polo also saw spectacular mud volcanos, sourced by natural gas seeping through ponds, and a flaming hillside, the "Eternal Fires of the Apsheron Peninsula", a spit of land that juts eastward from Azerbaijan into the Caspian Sea and where condensate and natural gas seeping through fractured shales has burned, and been worshipped, for centuries. The thumbnail on the right shows the Temple of the Fire Worshipers at Ateshkah where a gas seep has burned since ancient times.

When Marco Polo in 1264 visited the Persian city of Baku, on the shores of the Caspian Sea in modern Azerbaijan, he saw oil being collected from seeps. He wrote that "on the confines toward Geirgine there is a fountain from which oil springs in great abundance, inasmuch as a hundred shiploads might be taken from it at one time." In addition to oil seeps, Marco Polo also saw spectacular mud volcanos, sourced by natural gas seeping through ponds, and a flaming hillside, the "Eternal Fires of the Apsheron Peninsula", a spit of land that juts eastward from Azerbaijan into the Caspian Sea and where condensate and natural gas seeping through fractured shales has burned, and been worshipped, for centuries. The thumbnail on the right shows the Temple of the Fire Worshipers at Ateshkah where a gas seep has burned since ancient times.